The tiny Republic of the Marshall Islands recently filed an extraordinary lawsuit at the International Court of Justice in The Hague, suing all nine nuclear weapons possessors for failing to eliminate their nuclear arsenals. The legal basis of the case is derived from Article VI of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which obligates the five nuclear weapons states under the treaty (the United States, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, France, and the People’s Republic of China) “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament.”

The lawsuit also charges the four nuclear weapons states outside of the NPT—including one, Israel, which has never even acknowledged possessing nuclear weapons—with violating international customary law. But is this lawsuit more than a publicity gimmick? How seriously should it be taken? What does it tells us about current international nonproliferation regime?

The lawsuit also charges the four nuclear weapons states outside of the NPT—including one, Israel, which has never even acknowledged possessing nuclear weapons—with violating international customary law. But is this lawsuit more than a publicity gimmick? How seriously should it be taken? What does it tells us about current international nonproliferation regime?

It is easy, of course, to dismiss the lawsuit as an exercise in futility, or at best an act of moral inspiration that will have almost no political impact on the real world. In a sense, this assessment is flatly true. After all, only three of the nine nuclear states named by the lawsuit actually abide to the rulings of the International Court of Justice. Furthermore, the court tends to avoid making rulings on matters of national security, let alone on nuclear weapons-related matters (notwithstanding its 1996 advisory opinion on the legality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons). And, of course, all of this court’s rulings lack a means of enforcement.

Nevertheless, this unprecedented lawsuit highlights attitudes, perceptions, and strategies that are related to the politics of nuclear disarmament and are worth noting. The lawsuit reflects a growing belief among international legal and policy experts (as well as some diplomats) that the time has come for the NPT to be treated—due to its near universal adherence—as part of customary international law by which all states must abide, regardless of whether or not they actually signed the treaty.

Based on this reasoning, the Marshall Islands asks the International Court of Justice to rule that all nine nuclear states are in material breach of their legal obligation to disarm under international law, regardless of their status under the NPT. Currently the international community does not consider the NPT to be part of international customary law; if it were, the treaty would have a legal status similar to that of the international bans on slavery or torture. Should the International Court of Justice make such a ruling, it could elevate the discourse on nuclear disarmament from vague declarations of intentions to stark statements of legally binding commitment.

The lawsuit accentuates the rise of a new kind of politics of nuclear disarmament, a politics that ties nuclear disarmament to humanitarian issues. Linking humanitarian concerns to nuclear disarmament is, of course, not new; this connection has implicitly existed since nuclear weapons were introduced. In 2010, however, the linkage became explicit when humanitarian consequences were addressed in the NPT Review Conference final document. In 2013, the Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons in Oslo, Norway, started a series of international meetings on this theme. These conferences press the issue of nuclear disarmament through the lens of the unique characteristics of nuclear weapons—their capability for unleashing destruction not just on vast numbers of humans, but also on the environment, the economy, and the well-being of future generations. Notably, all five nuclear nations under the NPT and Israel refused to attend the first two humanitarian conferences and are unlikely to attend the next, calling them a distraction from the legitimate fora for disarmament negotiations.

The timing of the lawsuit is also significant. The Marshall Islands filed the suit after the second humanitarian consequences conference in Nayarit, Mexico, and a week before the NPT Preparatory Committee sessions in New York. It seems to be an attempt to use the momentum of the Nayarit conference to put the question of the legality of nuclear arsenals on the agenda at the Preparatory Committee meetings. So far, however, the attempt has not been successful. While a number of nongovernmental organizations have been vocal about the lawsuit, especially at NPT Preparatory Committee side events, the delegations participating in the conference have remained all but silent on the subject.

Finally, the Marshalls lawsuit is an effort to force the four non-NPT nuclear weapons countries (India, Israel, Pakistan, and North Korea) to accept the same status—and therefore have the same disarmament obligation—as the NPT nuclear weapons states. Israel has never even officially confirmed nuclear possession, and this lawsuit is arguably the first formal challenge of Israel’s policy of nuclear opacity, or amimut, by a non-Arab state. In arguing that the NPT falls under customary international law, the lawsuit maintains that all nuclear weapons states are legally required to begin negotiations in good faith towards nuclear disarmament.

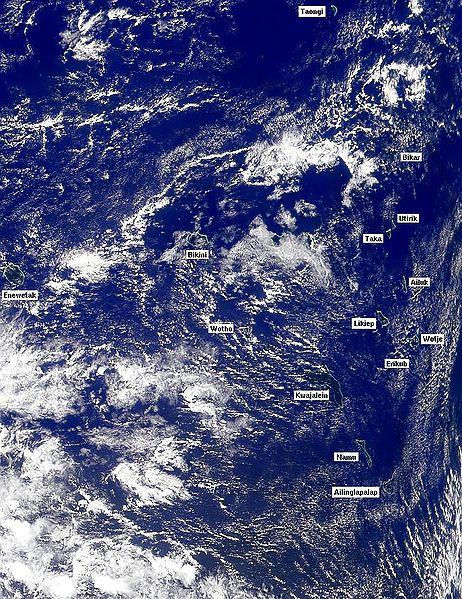

The lawsuit’s greatest symbolic strength is based on history; the Marshall Islands have firsthand knowledge of the consequences of nuclear weapons. From 1946 to 1958, the United States conducted 67 atmospheric nuclear tests in Marshall Islands territories in the Pacific. The hydrogen bomb test in 1954 forced the inhabitants of two of the Marshall Islands, Rongelap and Utrik, to evacuate, and the overall radiological damage done during these tests is still a matter of contention.

So the Marshall Islands’ lawsuit should be taken seriously to some extent, but not because of any short-term political impact. Rather, the importance of the lawsuit is based on its ability to highlight the emergence of a new politics of nuclear disarmament, a politics that challenges the very legitimacy and legality of nuclear weapons possession. The lawsuit is unlikely to change nuclear disarmament’s legal standing. It could, however, foster international public support for more concrete efforts toward nuclear disarmament. Whether this type of approach will gain significant traction in the public sphere—as the International Campaign to Ban Landmines did in 1997, leading to a global ban on land mines—remains to be seen. But the nuclear community should closely monitor the reactions to this lawsuit, because such a public response is, if not certain, at least now possible.