Kumar Sundaram

On the eve of India’s Republic Day, the Modi government has announced that it will arm-twist the public-owned General Insurance Company(GIC) to provide insurance cover for the nuclear suppliers. Though the exact details are still not clear, the media reports suggest that the Indian government has found a roundabout way to placate the US nuclear suppliers’ like Westinghouse and General Electric (GE) which have been lobbying to affect an amendment in the Nuclear Liability Act of 2010 ever since its inception. Touted as a big breakthrough during President Obama’s ongoing visit, this move is clearly a capitulation to their long-standing demand on the issue.

The Union finance minister was quoted as saying earlier this month that there are problems with the liability law. But the twist is, earlier the BJP saw a problem in letting the suppliers go scot-free and now it sees a problem in even the diluted clause holding the suppliers responsible.

The Act provides for a “right of recourse” to the operator, the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL), in case of a nuclear accident, for it to recover part of the liability from the foreign and domestic suppliers. Although the suppliers’ liability clause was resisted by the French, Russian and other foreign corporations as well as domestic companies looking for crumbs in the nuclear market, it is the US corporations, and the Obama administration on their behalf, that have been most vociferous in asking for a dilution of the suppliers’ liability clause, to escape a Bhopal-like situation. The reason is, the US nuclear industry is dominated by private players while other nuclear corporates like the French corporate Areva and the Atomsroyexport of Russia have state backing. While the French government said it was ok with the liability provisions and the Russian government agreed to it, albeit with some reservations, almost every single US dignitary – from Hilary Clinton to John Kerry – visiting India in last few years has called for doing away with the suppliers’ liability clause. The earlier Prime Minister, during his last visit to the United States, presented his government’s re-interpretation of the clause as being open-ended, providing a choice to the operator not to sue the supplier, and promised that India would chose not to use the legal option. However, this didn’t seem enough for the US government and it insisted on a clean exemption.

The Act provides for a “right of recourse” to the operator, the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL), in case of a nuclear accident, for it to recover part of the liability from the foreign and domestic suppliers. Although the suppliers’ liability clause was resisted by the French, Russian and other foreign corporations as well as domestic companies looking for crumbs in the nuclear market, it is the US corporations, and the Obama administration on their behalf, that have been most vociferous in asking for a dilution of the suppliers’ liability clause, to escape a Bhopal-like situation. The reason is, the US nuclear industry is dominated by private players while other nuclear corporates like the French corporate Areva and the Atomsroyexport of Russia have state backing. While the French government said it was ok with the liability provisions and the Russian government agreed to it, albeit with some reservations, almost every single US dignitary – from Hilary Clinton to John Kerry – visiting India in last few years has called for doing away with the suppliers’ liability clause. The earlier Prime Minister, during his last visit to the United States, presented his government’s re-interpretation of the clause as being open-ended, providing a choice to the operator not to sue the supplier, and promised that India would chose not to use the legal option. However, this didn’t seem enough for the US government and it insisted on a clean exemption.

The current push for looking for an Indian state-owned insurance cover is also an outcome of persistent American pressure. The Indian government started a process of reconsideration by setting up an India-US joint committee to find a way out of the ‘liability impasse’ and the US side suggested an “insurance-type” approach.

The BJP and nuclear liability –

Ironically, the insurance route to subvert the liability law is being resorted to by the BJP, which vehemently opposed moves to dilute the liability law while in opposition. The BJP in fact was opposed to the Act itself in 2010 as the suppliers’ liability is already very meagre. The BJP was earlier opposed to both the limiting of the liability as well as channeling it to the Indian taxpayer. The BJP then alleged that “the bill was being brought under US pressure mainly to keep the two American multinationals – Westinghouse and General Electric – from paying any liability and making the Indian government liable to pay in case of an accident.” Senior BJP leader Yashwant Sinha then had said – “clearly, the life of an Indian is only worth a dime compared to the life of an American.”

However, now the government and the nuclear establishment seem so worried about the concerns of suppliers and of the Indian law being a departure from the international convention channeling all liability to the operator, Sushma Swaraj, the current Foreign Minister, had earlier precisely called for an India-specific liability law. Ms. Swaraj had then likened the Indo-US nuclear deal to Jehangir allowing the British East India Company to do business in India. Other senior BJP leaders too termed any effort to dilute suppliers’ liability akin to an abject surrender of India’s sovereignty to the US.

Suppliers’ liability in the Indian law

The Indian nuclear industry worked without a liability law for the last 5 decades, because it wholly functioned as a state-owned enterprise. The liability law was brought in only in 2010, when the sector was opened to foreign players as suppliers. Going through the initial versions of the Bill before it became an Act, one can clearly see that the motive was more to protect the suppliers in case of an accident, than really providing potential Indian victims any relief that would be commensurate with the actual damage caused which can be incalculable.

However, it was the Supreme Court’s verdict on Bhopal in 2010, that exacerbated the situation causing public dismay over the subvertion of justice in the Bhopal case. This resulted in pressure from civil society and the opposition parties including the BJP, thereby insisting that a clause providing for a hook on suppliers to be inserted in the proposed nuclear liability Bill. The government initially tried to dilute Clause 17(b) by shamefully inserting an ‘intent’ sub-clause and other such tricks, which were strongly resisted. Remarkably, when the Nuclear Liability Bill came for discussion to the Parliament’s Standing Committee, secretaries of 8 ministries – including health, home and environment – registered their strong reservations. Ms. K Sujatha Rao, the then health secretary went public with her views – “forget drafting, we were not even consulted before the bill was sent to the Cabinet for approval.” India’s former nuclear regulator, Dr. A Gopalakrishnan poignantly highlighted the implications of such efforts to appease the foreign nuclear suppliers at every possible step by coming up with newer versions of Article 17(b).

The attempts to find a way to circumvent suppliers’ liability did not stop there. These included making supplier culpability dependent on an explicit mention of the liability provision in the bilateral contract between the supplier and the operator.In addition, the Indian government limited the product liability period to just 5 years under the Nuclear Liability Rules of 2011 which were designed to guide the implementation of 2010 Act. Eminent jurist Soli Sorabjee termed the Rules “ultra vires” of the Act and going against its spirit.

Liability is not a largesse

While the Indian nuclear liability regime remains far from providing adequate compensation to the victims, nuclear liability as such is not just a matter of ensuring compensation. It is also a mechanism to ensure that the companies adhere to best safety practices. The IAEA itself has underlined three roles played by nuclear liability mechanisms — to protect the public, to safeguard the environment, and to enhance nuclear safety. After Fukushima, the need to revisit and revise the nuclear liability regulations has been widely recognised. As Mark Cooper noted in his article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists,

When governments socialize risk — shift it from the private sector to the public — they create what economists call moral hazard. This is the hazard that the private actor, who no longer bears the risk, will do more risky things than he would have done, if he had borne the full liability of his actions. It is a moral problem; the irresponsible actions of one person or entity harm an innocent bystander. It is also an economic problem because it induces firms to engage in uneconomic activities.

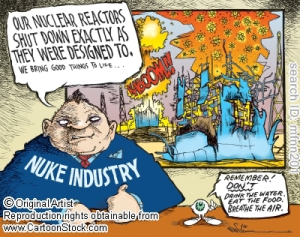

The nuclear industry has made every attempt to minimize its liability internationally. There are primarily two reasons for this. Firstly, because the higher liability would make their insurance coverage prohibitively expensive. This also underlines the fact that nuclear energy is not really viable as a purely private economic enterprise. Secondly, if the amount of nuclear liability is calculated correctly, it would also reveal the astronomical economic cost of nuclear accidents. While the most conservative estimates for the clean-up of Fukushima accident are around $250 billion, the total cost of Chernobyl was over 600 billion US dollars.

Privatising profits, socialising risks

Another question that must be asked here is, if the Modi government has so much faith in the forces of the market, why is a publicly-owned Indian insurance company being made to secure financial protection for foreign as well as domestic nuclear corporations? When private insurance companies have been pushing for reforms, encouragement and greater slice of the market, why don’t they come forward and provide insurance for the big players of the nuclear industry? As it has been asked several times by independent experts, if the nuclear industry wants people to trust their claims on safety and not hesitate to thereby in effect put their lives at stake, why is it not ready to put its money where its mouth is?

The international suppliers evading liability in the still unfolding Fukushima accident is an instructive case. As the estimates of decontamination and decommissioning costs continue to rise, more than 4000 individuals initiated collective litigation last year in Japan to sue GE, Toshiba and Hitachi, the manufacturers and suppliers of Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power station. On the contrary, the Japanese government, hand-in-gloves with the industry, has been trying to pass the burden on to the public at large. Even the decommissioning costs could be passed on to all power customers, making it harder for the new renewable energy entrants to compete and sustain themselves.

The world over, the nuclear industry has been known to evade liability and insurance. Internationally, it has insisted on placing limitations on the amount, duration and types of damages when it comes to accepting liability, and has pressed for an international regime channelling all liability exclusively to the operators. In the US, its Congress socialized the cost of nuclear accidents with the Price-Anderson Nuclear Indemnity Act of 1957 under which the utilities are required to carry a small amount of private insurance and create an industry-wide pool of about $12 billion for accident relief.

Despite the previous government being a coalition and also willing to serve the US nuclear lobby’s interests, it was the strength of Indian democracy at work, that enacted a law safeguarding the interests of Indian citizens. The efforts of civil society, of independent voices, smaller parties in the last ruling coalition and of the opposition including the BJP, resulted in ensuring a minimum protection for potential victims. What is happening now is a case of a supposedly strong Prime Minister, enjoying overwhelming majority, going out of his way to placate the interests of the American nuclear lobby. The electoral majority of the government is being used to find a way out for the US corporations, undermining the constitutionally mandated Liability Act of the sovereign Indian parliament. So much for ‘Make in India’!

The author is a researcher, associated with the Coalition for Nuclear Disarmament and Peace (CNDP). He can be contacted at pksundaram@gmail.com