By Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, Mackenzie Knight | September 5, 2024

India continues to modernize its nuclear arsenal, with at least four new weapon systems and several new delivery platforms under development to complement or replace existing nuclear-capable aircraft, land-based delivery systems, and sea-based systems. Several of these systems are nearing completion and will soon be fielded. We estimate that India may have produced enough military plutonium for 130 to 210 nuclear warheads but likely has produced only around 172, although the country’s warhead stockpile is likely growing. The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by the staff of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project: director Hans M. Kristensen, associate director Matt Korda, senior research associates Eliana Johns and Mackenzie Knight.

This article is freely available in PDF format in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ digital magazine (published by Taylor & Francis) at this link. To cite this article, please use the following citation, adapted to the appropriate citation style: Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, Indian nuclear weapons, 2024, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 80:5, 326-342, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2024.2388470

To see all previous Nuclear Notebook columns in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists dating back to 1987, go to https://thebulletin.org/nuclear-notebook/.

India continues to modernize its nuclear weapons arsenal and operationalize its nascent triad. We estimate that India currently operates eight different nuclear-capable systems: two aircraft, five land-based ballistic missiles, and one sea-based ballistic missile. At least five more systems are in development, most of which are thought to be nearing completion and to be fielded with the armed forces soon.

Research methodology and confidence

The Indian government does not publish numbers about the size of its nuclear weapon stockpile. The analyses and estimates made in the Nuclear Notebook are therefore derived from a combination of open sources: (1) state-originating data (e.g. government statements, declassified documents, budgetary information, military parades, and treaty disclosure data); (2) non-state-originating data (e.g. media reports, think tank analyses, and industry publications); and (3) commercial satellite imagery. Because each of these sources provides different and limited information that is subject to varying degrees of uncertainty, we crosscheck each data point by using multiple sources and supplementing them with private conversations with officials whenever possible.

Collecting and analyzing accurate information about India’s nuclear forces is a more challenging effort than for many other nuclear-armed states. India has never disclosed the size of its nuclear stockpile, and Indian officials do not regularly comment on the capabilities of the country’s nuclear arsenal. Although some official information can be derived from parliamentary inquiries, budget documents, government statements, and other sources, India generally maintains a culture of relative opacity regarding its nuclear arsenal. India has previously refused to divulge the costs of certain nuclear weapon programs, and in 2016, the Indian government added Strategic Forces Command to a list of security organizations exempt from India’s Right to Information Act, thereby inhibiting journalists, researchers, and the public from getting access to critical information about India’s nuclear arsenal (Government of India 2016; Sarkar 2021). In addition, in contrast to geopolitical competitors like China or Russia, the United States does not typically publish assessments of India’s nuclear arsenal; one US Air Force publication that used to provide information has not been published since early 2021, and that version appeared to include information that was watered down and out of date.

While the Indian government rarely provides official statements about its nuclear arsenal, the Ministry of Defence’s Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) often publishes useful details about the weapon systems that it is developing. These details can be found in monographs, monthly reports, and other publications. While these reports very rarely include details specifically about India’s nuclear program, they sometimes offer data points about dual-capable delivery systems that can be leveraged for analysis.

In the absence of much official information from the Indian government and military and from Western governments, local news and media outlets tend to embellish details about the country’s nuclear arsenal. For example, some outlets regularly claim that certain weapon systems are “nuclear-capable,” despite a lack of any official evidence to that effect. Many news publications also tend to rely on anonymous “sources” for military information without indicating or providing evidence that these sources have actual familiarity with the systems that they are describing.

To that end, we generally rely on official sources and images—as well as commercially or freely-available satellite imagery—to analyze India’s nuclear arsenal and, whenever possible, try to corroborate the credibility of any unofficial claims with multiple sources. Satellite imagery can be particularly useful in monitoring construction at military facilities, as well as identifying which types of missiles, vessels, or aircraft are present at bases. In particular, the research of open-source analysts, such as @tinfoil_globe on the social media platform X (formerly Twitter), has proven to be highly valuable in analyzing Indian military bases using satellite imagery. In certain cases, useful imagery about nuclear systems can also be obtained through social media posts—both from military and civilian accounts—and can be used in conjunction with satellite imagery for more concrete analysis.

Fissile material and warhead inventory estimates

India is one of only a handful of countries believed to be producing both highly enriched uranium (HEU) and weapons-grade plutonium, although its HEU production is largely assumed to be focused on producing fuel for its growing number of nuclear-powered vessels and submarines (Frieß et al. 2024).

India’s source of weapons-grade plutonium has been the operational Dhruva plutonium production reactor at the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre complex near Mumbai, and until 2010 the CIRUS reactor at the same location. In March 2024, after more than a decade of delays, India also completed construction and initiated the core loading of its first unsafeguarded 500-megawatt Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor at the Indira Gandhi Centre for Atomic Research near Kalpakkam (Department of Atomic Energy, 2024). The new reactor produces more plutonium 239 than it consumes during the fission process, and therefore could increase India’s future plutonium production significantly if the reactor is operated effectively. The director of the research center has additionally stated that six more fast breeder reactors will come online within the next 15?years (Kumar 2018).

As of the beginning of 2023, the International Panel on Fissile Materials estimated India to have produced approximately 680 kilograms (plus or minus about 160 kilograms) of weapon-grade plutonium (Frieß et al. 2024). Assuming approximately four kilograms of plutonium per warhead, this would theoretically be sufficient for producing anywhere between 130 and 210 nuclear warheads. However, there are some caveats that come with this calculation due to several uncertainties. Most notably, it is unclear whether India is prioritizing the development and production of higher-yield thermonuclear weapons, lower-yield fission-only weapons, boosted single-stage weapons, or any combination of these designs; these could all use different amounts of plutonium enriched to different levels. India’s 1998 nuclear tests reliably validated a fission design, but the country’s progress on boosted fission and thermonuclear weapon designs remains highly uncertain (Albright 1998; Levy 2015). It is also likely that India has not used all its plutonium to produce warheads but may have kept some in reserve.

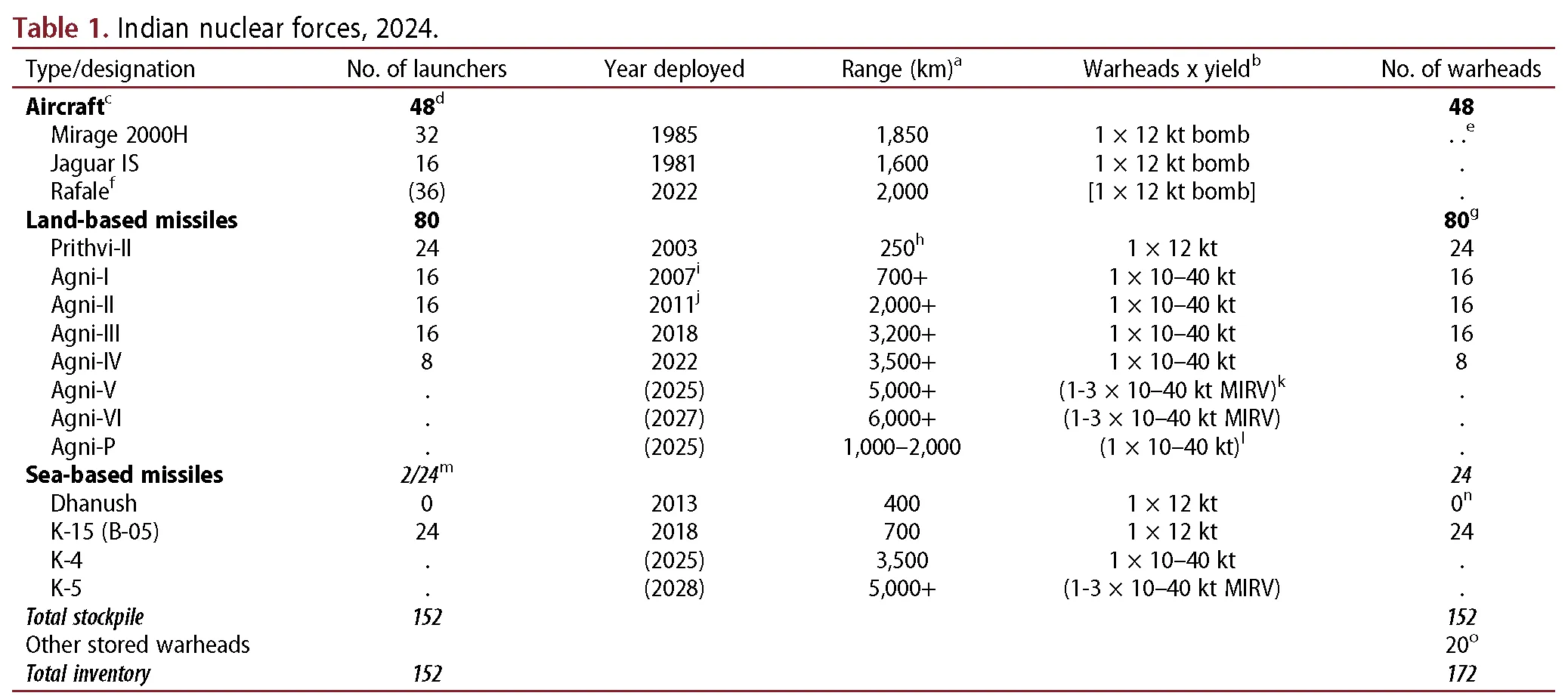

The size of India’s nuclear stockpile also depends on the number and types of launchers that can deliver them, as it is unlikely that most nuclear-armed states would produce significantly larger numbers of warheads than they can actually launch. Based on available information about its nuclear-capable delivery force structure and strategy, we estimate that India has produced around 172 nuclear warheads (see Table 1). It will need more warheads to arm the new missiles that it is currently developing.

Nuclear doctrine

Tensions between India and Pakistan constitute one of the most concerning nuclear hotspots on the planet. These two nuclear-armed countries engaged in open hostilities as recently as November 2020, when Indian and Pakistani soldiers exchanged artillery and gunfire over the Line of Control, resulting in at least 22 deaths. The clash followed another incident in February 2019, when Indian fighters dropped bombs near the Pakistani town of Balakot in response to a suicide bombing conducted by a Pakistan-based militant group. In retaliation, Pakistani aircraft shot down and captured an Indian pilot before returning him a week later. The skirmish escalated into the nuclear realm when it triggered a convening of Pakistan’s National Command Authority, the body that oversees Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal. Speaking to the media at the time, a senior Pakistani official noted: “I hope you know what the [National Command Authority] means and what it constitutes. I said that we will surprise you. Wait for that surprise.… You have chosen a path of war without knowing the consequence for the peace and security of the region” (Abbasi 2019).

In this context, the risk of conflict escalation between India and Pakistan remains dangerously high. In March 2022, India accidentally launched what appeared to be a BrahMos conventional ground-launched cruise missile 124 kilometers into Pakistani territory, damaging civilian property. Pakistani officials subsequently claimed that India did not alert them using the high-level military hotline, and India did not even issue a public statement about the accident until two days later (Dawn 2022). In the absence of any de-escalation measures from India, Pakistan reportedly suspended all military and civilian aircraft for nearly six hours and placed frontline bases and strike aircraft on high alert (Bhatt 2022). If this same accidental launch had taken place during a period of heightened tensions, it is possible that the incident could have escalated into a very dangerous phase (Korda 2022).

While India’s primary deterrence relationship historically has been with Pakistan, its nuclear modernization indicates that it is putting increased emphasis on its future strategic relationship with China. In November 2021, the then-Indian Chief of Defence Staff stated in a press conference that China had become India’s biggest security threat (Sen 2021). Additionally, nearly all of India’s new Agni missiles have ranges that suggest China is their primary target. This posture is likely to have been reinforced after the 2017 Doklam standoff during which Chinese and Indian troops were placed on high alert over a dispute near the Bhutanese border. Tensions have remained high in subsequent years, particularly following another border skirmish in June 2020 that resulted in the deaths of both Chinese and Indian soldiers. Further casualties have been reported due to Chinese-Indian military skirmishes as recently as January 2021 (BBC 2021).

The expected expansion of India’s nuclear forces increasingly focused on a militarily superior China (in terms of both conventional and nuclear forces) will result in new capabilities being deployed over the next decade. This development could potentially also influence how India views the role of its nuclear weapons against Pakistan. According to one analyst, “[W]e may be witnessing what I call a ‘decoupling’ of Indian nuclear strategy between China and Pakistan. The force requirements India needs in order to credibly threaten assured retaliation against China may allow it to pursue more aggressive strategies—such as escalation dominance or a ‘splendid first strike’—against Pakistan” (Narang 2017). (A “splendid first strike” is an initial attack with nuclear weapons that completely disables the enemy’s nuclear capability, ensuring that there will be no retaliation).

India has long adhered to a nuclear no-first-use policy. This policy, however, was weakened by India’s 2003 declaration that it could potentially use nuclear weapons in response to chemical or biological attacks—which would therefore constitute nuclear first use, even if it were in retaliation. Moreover, amid the 2016 border skirmishes with Pakistan, India’s then-defense minister Manohar Parrikar indicated that India should not “bind” itself to the no-first-use policy (Som 2016). Although the Indian government later explained that the minister’s remarks represented his personal opinion, the debate highlighted the conditions under which India would consider using nuclear weapons. Current defense minister Rajnath Singh has also publicly questioned India’s future commitment to its no-first-use policy, tweeting in August 2019 that “India has strictly adhered to this doctrine. What happens in the future depends on the circumstances” (R. Singh 2019). Recent scholarship has further called India’s commitment to its no-first-use policy into question, with some analysts asserting that “India’s NFU [no-first-use] policy is neither a stable nor a reliable predictor of how the Indian military and political leadership might actually use nuclear weapons” (Sundaram and Ramana 2018). Despite questions about the future of India’s NFU policy, it might have served to limit somewhat the scope and strategy of Indian nuclear forces for the first two decades of its nuclear era.

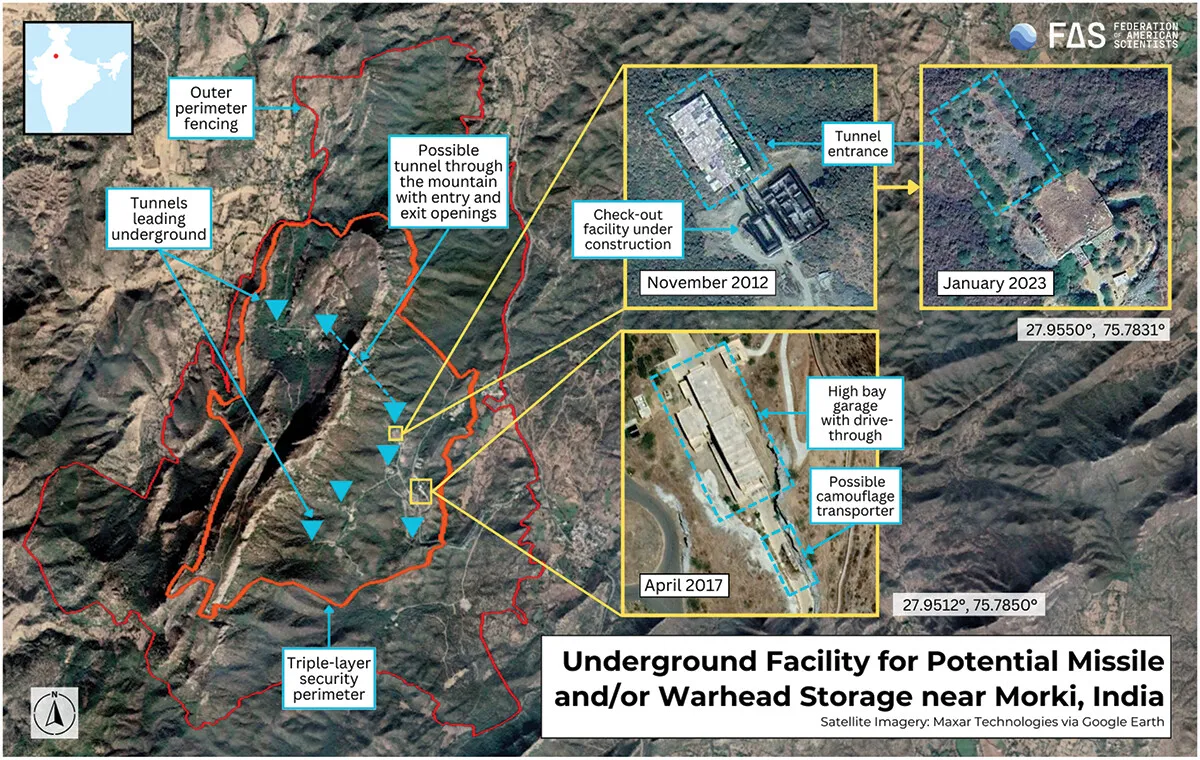

Additionally, although India has long been thought to store its nuclear warheads separately from deployed launchers, some analysts have suggested that at least some nuclear bombs are co-located with aircraft on bases in underground bunkers for rapid mating if necessary and that India might be moving toward “pre-mating” some warheads with ballistic missiles in canisters for a subsection of the missile force (Narang 2013). The term “pre-mating” appears to imply the warhead is not actually mated with the missile but in a near-complete status nearby so the warhead can be readied and mated on short notice if needed. Before mating, the warheads would have to be brought out from storage and mated with the missile in a special handling facility. One potential but unconfirmed candidate for such a facility is located near Morki (Figure 1).

There is still uncertainty about the readiness of the arsenal on a day-to-day basis, not least because the only two canisterized missiles—Agni-V and Agni-P—are not yet operationally deployed, and India’s only deployed submarine appears currently to be more of a training platform and technology demonstrator. But this trend may deepen with deployment of operational canisterized launchers and India’s development of a sea-based leg of its nuclear triad, which for the United States and Russia has typically involved mating warheads with missiles.

Aircraft

Fighter-bombers were India’s first and only nuclear strike force until 2003, when the Prithvi-II nuclear-capable ballistic missile was fielded. Despite considerable progress since then in building a diverse arsenal of land-and sea-based ballistic missiles, aircraft continue to serve a prominent role as a flexible strike force in India’s nuclear posture. We estimate that three or four squadrons of Mirage 2000H and Jaguar IS aircraft at three bases are assigned nuclear strike missions against Pakistan and China.

The Mirage 2000H Vajra (“divine thunder”), which is likely India’s primary nuclear strike aircraft, is deployed with the 1st, 7th, and possibly the 9th squadrons of the 40th Wing at Maharajpur (Gwalior) Air Force Station in northern Madhya Pradesh. We estimate that one or two of these squadrons has a secondary nuclear mission. Indian Mirage aircraft also occasionally operate from the Nal (Bikaner) Air Force Station in western Rajasthan, and other bases might potentially function as nuclear dispersal bases as well.

The Indian Mirage 2000H, which was originally supplied by France, is undergoing upgrades to extend its service life and enhance its capabilities to include new radar, avionics, and electronic warfare systems. India signed a $2.1 billion deal with French company Thales in 2011 to upgrade 51 Mirage 2000H aircraft to the Mirage 2000–5 standard. Although the modernization program was scheduled to be completed by the end of 2021, the program is behind schedule, with only about half of the aircraft having been modernized by the expected deadline (Philip 2022). India does not have domestic manufacturing capability for the Mirage aircraft, and as France phases out Mirage aircraft in favor of the new Rafale aircraft, India will face difficulties in maintaining its fleet. To maintain its existing fighter jets for another decade, India’s Air Force signed deals with France in 2020 and 2021 for a total of 40 Mirage 2000 aircraft that have been phased out of the French Air Force. India will use the scavenged parts to upkeep its existing Mirage squadrons (Yelwe 2024). India is also reportedly in discussions with Qatar for the purchase of 12?second-hand Mirage 2000-5 aircraft, which officials stated would be for flying operations, not spare parts (Hindustan Times 2024a).

The Indian Air Force also operates four squadrons of Jaguar IS/IB Shamsher (“Sword of Justice”) aircraft at three bases (a fifth squadron flies the naval IM version). These include the 5th and 14th squadrons of the 7th Wing at Ambala Air Force Station in northwestern Haryana, the 16th and 27th squadrons of the 17th Wing at Gorakhpur Air Force Station in northeastern Uttar Pradesh, and the 6th and 224th squadrons of the 33rd Wing at Jamnagar Air Force Station in southwestern Gujarat. We estimate that one or two of the squadrons at Ambala and Gorakhpur (one at each base) might be assigned a secondary nuclear strike mission. Jaguar aircraft also occasionally operate from the Nal (Bikaner) Air Force Station in western Rajasthan. The Jaguar, designed jointly by France and Britain, was nuclear-capable when deployed by those countries.

The Indian Air Force has operated the Jaguar since the 1980s. Due to its age, the aircraft might be retired from the nuclear mission soon if it has not been already. Half of the Jaguars have received the so-called DARIN-III precision-attack and avionics upgrade since 2017 (Ministry of Defence 2017), but the upgrade of the second half of the inventory was scrapped in August 2019 due to its prohibitive cost and long timeline. Instead, the Indian Air Force will reportedly phase out its Jaguar fleet over the next 10?years. In October 2019, India’s Air Chief Marshal declared that the Indian Air Force’s six Jaguar squadrons of approximately 108 fighters would begin retiring in early 2020 (Shukla 2019); however, this was pushed back, potentially to bring India closer to its goal of maintaining enough squadrons to simultaneously deter both Pakistan and China over the coming decade (Shukla 2021a). In 2023, the Indian Air Force outlined its plans for retiring the Jaguar starting in 2027–2028. The plan includes a phased approach with complete retirement expected by 2035. India plans to replace the Jaguar with the indigenously produced Tejas Mark 2 (Mk-2) fighter jet currently under development (Kunde 2023).

On September 23, 2016, India and France signed an agreement for delivery of 36 Rafale aircraft (Ministry of Defence 2017). The order was considerably reduced from initial plans to buy 126 Rafales. The Rafale is used for the nuclear mission in the French Air Force, and India could potentially convert it to serve a similar role in the Indian Air Force, with an eye toward taking over the air-based nuclear strike role in the future. The Indian defense minister formally received the first Rafale (tail number RB-001) at a special ceremony in France in October 2019, and the full shipment of 36 aircraft was completed on-schedule by April 2022 (Hindustan Times 2022). All 36 Rafales are outfitted with 13 “India-Specific Enhancements,” which include new radars, cold-weather engine start-up devices, 10-hour flight data recorders, helmet-mounted display sights, and electronic warfare and friend-or-foe identification systems (Dominguez 2019).

The Rafales are being deployed in two equally sized squadrons of 18 fighters and four dual-seat trainers: one squadron (17th “Golden Arrows” Squadron) at Ambala Air Base Station, located only 220 kilometers from the Pakistani border, and the other squadron (101st “Falcons of Chamb and Akhnoor” Squadron) at Hasimara Air Force Station in West Bengal. New infrastructure developments to accommodate the planes are being constructed at both bases, and the Indian Air Force has reinstated the squadrons to active duty after they had both been decommissioned years earlier (Indian Air Force 2021).

As of July 2024, French manufacturer Dassault Aviation SA is reportedly advancing plans to construct a Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul (MRO) facility near Jewar International Airport, which will allow India to locally manufacture future Rafale aircraft as part of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s “Make In India” initiative. Engine manufacturer Safran SA also has plans to build an MRO facility at Hyderabad for Rafale engines (Gupta 2024).

The Indian and French governments began negotiations in May 2024 for the purchase of 26 Rafale Marine fighter jets to operate from India’s INS Vikrant and INS Vikramaditya aircraft carriers (The Economic Times 2024a).

Land-based ballistic missiles

The Indian Army possesses five types of mobile land-based, nuclear-capable ballistic missiles that appear to be operational: the short-range Prithvi-II and Agni-I, the medium-range Agni-II, and the intermediate-range Agni-III and Agni-IV. At least two other Agni missiles are in development and nearing deployment: the medium-range Agni-P and the intermediate-range Agni-V. A new intercontinental-range Agni-VI missile is also thought to be in the design stage, although its status is unclear.

It remains to be seen how many of these missile types India plans to keep in its arsenal. Some may serve as technology development programs toward longer-range missiles. While the Indian government has made no statements about the future size or composition of its land-based missile force, it is possible that redundant missile types could potentially be discontinued or that only medium- and long-range missiles might be deployed in the future to provide a mix of strike options against Pakistan and China. Unconfirmed reports have also hinted that India could reconfigure some of its nuclear medium-range ballistic missiles for conventional strike roles, though it is unclear if and when this may happen due to the lack of additional information (Dubey 2023). In any case, the government appears to be planning to field a diverse missile force and may have around 80 operational land-based missiles as of July 2024.

The process for deploying Indian missiles is relatively opaque and uses some specific terms that are not used in other countries, which makes it more complex to piece together. Based on media reporting, press statements, and development timelines, the process appears to be as follows: Following the design and development of the missile by India’s DRDO, missile systems undergo design and successive development trials, followed by pre-induction flight tests and night launches. This usually takes several years and is accomplished in collaboration with the Strategic Forces Command, which is part of India’s Nuclear Command Authority and is responsible for operating and managing India’s nuclear weapons. Then, after typically three to five trials to validate the missile’s flight and technological systems, the missiles can be “inducted” into service, which means they are handed over to the armed forces. “Induction,” however, does not mean the missiles are operational, as they require additional user trials to achieve operational deployment status.

The short-range Prithvi-II missile was India’s first missile to be developed under the “Integrated Guided Missile Development Program” for nuclear deterrence, according to the Indian government (Press Information Bureau 2013). The missile can deliver a nuclear or conventional warhead to a range of 350 kilometers. Given the relatively small size of the Prithvi missile (nine meters long and one meter in diameter), the launcher is difficult to spot in satellite images and little is known about its deployment locations. It is thought India has four Prithvi missile groups (222, 333, 444, and 555) of which an estimated 24 launchers may have a nuclear mission. Potential locations include Jalandhar in Punjab, as well as Banar, Bikaner, and Jodhpur in Rajasthan.

The two-stage, solid-fuel, road-mobile Agni-I missile became operational in 2007, three years after its induction into the armed forces. The short-range missile can deliver a nuclear or conventional warhead to a distance of approximately 700 kilometers. The mission of Agni-I is thought to be focused on targeting Pakistan; we estimate that around 16 launchers are deployed in western India, possibly including the 334th Missile Group. In September 2020, India used an Agni-I booster to conduct a test of its developmental scramjet-powered Hypersonic Technology Demonstrator Vehicle (Jha 2020). Satellite imagery from September 2023 appears to show two Agni-I transporters at a garrison near Jodhpur, although it is unclear whether this is a temporary visit or semi-permanent deployment. In 2023, India conducted test launches of the Prithvi-II and the Agni-I, both of which were described by the Indian Ministry of Defence as “proven systems” (Government of India 2023a; 2023b).

The two-stage, solid-fuel, rail-mobile Agni-II—an improvement on the Agni-I—can deliver a nuclear or conventional warhead to a distance of more than 2,000 kilometers. The missile may have been inducted into the armed forces in 2008, but technical issues delayed its operational capability until 2011. Around 16 launchers are thought to be deployed in northern India, possibly including the 335th Missile Group. Targeting is probably focused on western, central, and southern China. Although the Agni-II appeared to suffer from technical issues and failed several of its previous test launches, more recent successful tests in 2018 and 2019 indicate that previous technical issues could have since been resolved (The Hindu 2019; Liu 2018).

The Agni-III—a two-stage, solid-fuel, rail-mobile, intermediate-range ballistic missile—can deliver a nuclear warhead to a distance of over 3,200 kilometers. Following its first failed night trial in 2019, India conducted a second night trial on November 23, 2022, which was successful (Rout 2022). We estimate around 16 Agni-III launchers are deployed, though the full operational status is uncertain. The longer range potentially allows India to deploy the Agni-III units further back from the Pakistani and Chinese borders, which would make it the first missile to bring Beijing within range of Indian nuclear weapons.

India has also deployed the Agni-IV missile—a two-stage, solid-fuel, road-and rail-mobile intermediate-range ballistic missile with the capability to deliver a single nuclear warhead to a distance of over 3,500 kilometers (Ministry of Defence 2014). Following its final development test in 2014, the Strategic Forces Command has since conducted four user launches, the most recent taking place in June 2022 (Government of India 2022).

Although the Agni-IV will be capable of striking targets in nearly all of China from locations in northeastern India, the Strategic Forces Command is also in the process of inducting the longer-range Agni-V—a three-stage, solid-fuel, road-mobile, near-intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capable of delivering a warhead to a distance of less than 6,000 kilometers. The extra range will allow the Indian military to establish Agni-V bases in central and southern India, further away from the Chinese border.

The Agni-V missile will bring another important new capability to the Indian strike force. The Agni-V is carried in a sealed canister on the launcher, meaning the warhead can be permanently mated with the missile, which is stored in a sealed, climate-controlled tube, instead of having to be installed prior to launch (Korda and Kristensen 2021). The first two test-launches used a rail launcher, but since 2015, all launches have been conducted from a road-mobile launcher. The launcher, which is known as the Transport-cum-Tilting vehicle-5 (TCT-5), is a 140-ton, 30-meter, 7-axle trailer pulled by a 3-axle Volvo truck (DRDO Newsletter 2014). The canister design “will reduce the reaction time drastically… just a few minutes from ‘stop-to-launch,’” the former head of India’s Defence Research and Development Organisation said in 2013 (Times of India 2013). Several Agni-V transporter erector launchers (TELs) are clearly visible at various points in time on commercial satellite imagery of DRDO’s integration center north of Hyderabad, as well as at other sites (see Figure 1 of the 2022 India Nuclear Notebook; Kristensen and Korda 2022).

In 2021, India conducted the first test-launches of its two-stage, solid-fuel, Agni-P medium-range ballistic missile with a range between 1,000 and 2,000 kilometers, which the Indian Government refers to as a “new generation” nuclear-capable ballistic missile (Government of India 2021b). The Agni-P is India’s first shorter-range ballistic missile to incorporate more sophisticated rocket motors, propellants, avionics packages, and navigation systems found in India’s newer, longer-range missiles like the Agni-IV and Agni-V. Importantly, the Agni-P is also carried in a sealed canister, similarly to the Agni-V (Korda and Kristensen 2021). One senior DRDO official remarked during the early stages of the Agni-P’s development that, “As our ballistic missiles grew in range, our technology grew in sophistication. Now the early, short-range missiles, which incorporate older technologies, will be replaced by missiles with more advanced technologies. Call it backward integration of technology” (Shukla 2016). Statements like these, coupled with the Agni-P’s clear capability upgrade over the early Agni-I and Agni-II missiles—which utilize older and less robust propellants, airframes, and hydraulic actuators, as well as less accurate guidance systems—suggest that the Agni-P will eventually replace older missiles once it becomes operational (Shukla 2021b). The Agni-P’s second pre-induction night trial was successfully conducted in April 2024 (The Economic Times 2024b). The missile system will likely undergo a few more tests before being officially inducted by the Strategic Forces Command.

India is also developing a conventional short-range ballistic missile (SRBM) known as the Pralay that is reportedly intended to take over the conventional role currently occupied by the dual-capable Prithvi-II and Agni-I SRBMs (Government of India 2021a; Unnithan 2021). If the nuclear and conventional short-range missions are split between the new Agni-P and Pralay missiles, respectively, that could help reduce the risk of misunderstanding in a conflict caused by mixing nuclear and conventional capabilities on the same platform. This could be further bolstered by the fact that the new Agni-P will likely be operated by Strategic Forces Command while the Pralay will be operated by the Indian Army’s artillery corps (Philip 2021).

For several years it has been rumored that India was developing the ability to deliver multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) on ballistic missiles. Finally, in March 2024, the Indian government announced that it had conducted the first flight test of its Agni-V ballistic missile “with Multiple Independently Targetable Re-Entry Vehicle (MIRV) technology” under what it called “Mission Divyastra” (Government of India 2024). While there will likely be additional flight tests before the Agni-V’s MIRV capability becomes fully operational, this initial test already marks significant technical progress and represents a notable change in India’s nuclear capabilities (Kristensen and Korda 2024). However, loading multiple warheads on the Agni-V would likely reduce its extended range, which was a key driver behind the initial development of the missile. The Agni-V is estimated to be capable of delivering a payload of 1.5 tons (the same as the Agni-III and -IV), and India’s first- and second-generation warheads—even the modified versions—are thought to be relatively heavy compared with warheads developed by other nuclear-armed states that also deploy MIRVs. As a result, we estimate Agni-V might only carry a small number of warheads, likely no more than three.

The Agni-P was also rumored to have been tested with maneuverable decoys in 2021 to simulate MIRV technology (Korda and Kristensen 2021). Reportedly, the Agni-P can also be equipped with a Maneuverable Reentry Vehicle (MaRV), though there has been no official confirmation of this capability (Desai 2022; Thakur 2024). Equipping a medium-range ballistic missile with MIRV technology would be odd from a strategic and operational standpoint; we therefore assume the 2021 test was intended to further advance India’s development of MIRV technology and decoys, rather than developing the capability to launch MIRVs from this specific system.

Deploying missiles with multiple warheads also invites questions about the credibility of India’s minimum deterrent doctrine. In other countries, MIRV technology was developed to increase the number of targets that can be attacked, overwhelm missile defenses, or both. Deploying MIRVs would reflect a strategy to swiftly strike multiple targets simultaneously and, as a result, signal an intention to quickly increase the size of the nuclear arsenal. In turn, it could potentially incite Pakistan and China to further increase their own arsenals. Unless China develops an effective missile defense system with capability against intermediate-range ballistic missiles, there seems to be little military need for MIRVs on Indian missiles (Kristensen 2013). It seems likely, however, that China’s deployment of MIRVs on some of its ICBMs and Pakistan’s development of the new Ababeel medium-range ballistic missile with MIRVs have increased support in India to also develop a MIRV capability, if for no other reason than to avoid falling behind in technological capability.

A few years ago, Ministry of Defence officials indicated that India’s strategic missile force will be “capped for the present with the Agni-V, with no successor or next series on the horizon or even on the drawing board” (Gupta 2018). However, India is rumored to have begun development of a new ICBM, known as Agni-VI. Official data on this missile is scarce, but an article posted on the government’s Press Information Bureau website in December 2016 claimed the Agni-VI “will have a strike-range of 8,000–10,000 kilometers” and will “be capable of being launched from submarines as well as from land” (Ghosh 2016). The US Air Force’s National Air and Space Intelligence Center estimates its range to be closer to 6,000 kilometers (National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2020). The development of an Agni-VI missile with a range of 8,000–10,000 kilometers—if confirmed—would be particularly controversial because it would extend well beyond potential regional targets in Pakistan and China. In 2023, a scientist who had previously worked at the DRDO reportedly claimed that the Agni-VI’s indigenously designed launcher had already undergone a successful test. However, the claim was revealed during the scientist’s trial on charges of espionage and should be treated with caution (Inamdar and Joshi 2023).

In addition, India is thought to be developing a land-based version of the short-range K-15 submarine launched ballistic missile (SLBM), known as the Shaurya. Due to the high level of uncertainty regarding this system, it is not included in our stockpile estimates.

Sea-based ballistic missiles

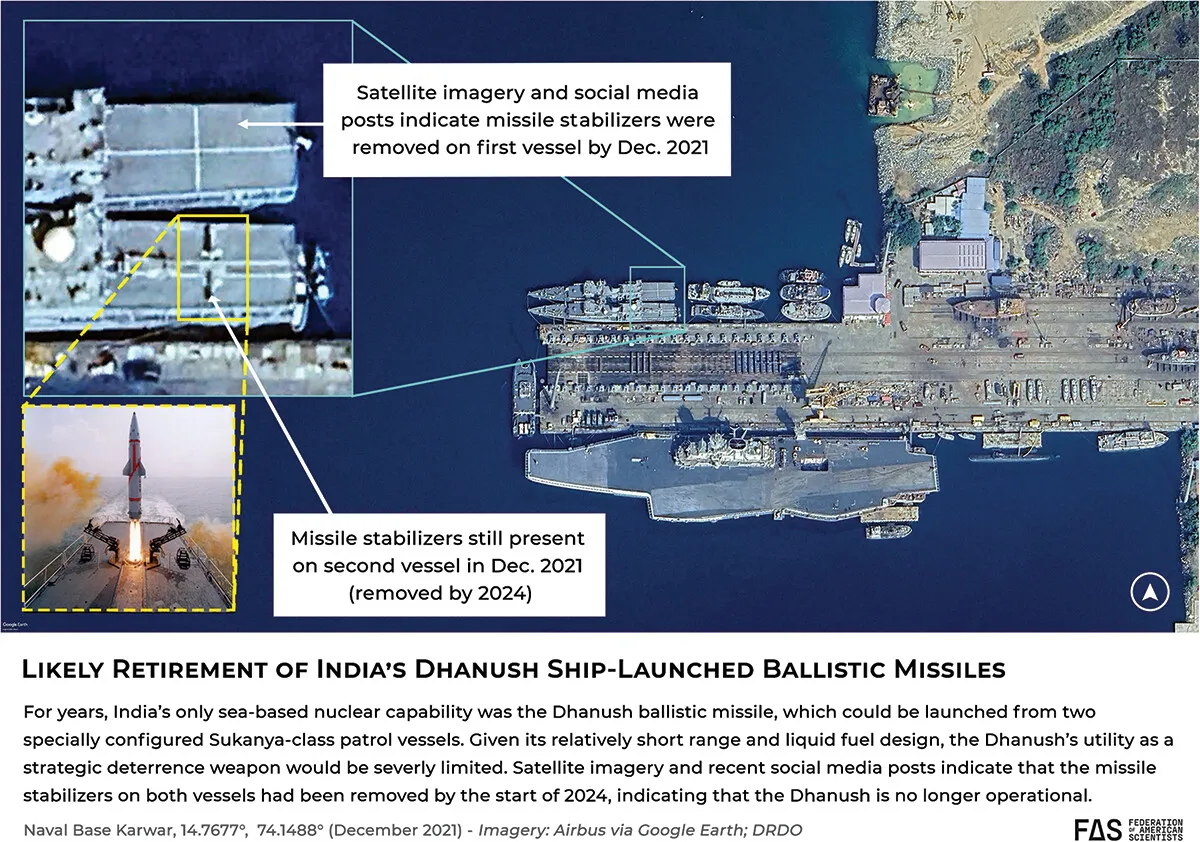

For years, India’s only sea-based nuclear capability was the Dhanush ballistic missile, a variant of its short-range Prithvi-II ballistic missile design. These missiles could be launched from the back of two specially configured Sukanya-class patrol vessels (P51 Subhadra and P52 Suvarna) with onboard flame diverters so that launches would not damage the ships. Given their relatively short ranges and liquid-fuel designs—meaning that they would need to be fueled immediately prior to launch—the Dhanush’s utility as a strategic deterrence weapon would be severely limited. The ships carrying these missiles would have to sail dangerously close to the Pakistani or Chinese coasts to target facilities in those countries, making them vulnerable to counterattack. The two Sukanya-class ships are homeported at the Karwar naval base on the Indian west coast.

The status of the Dhanush missile is unknown, but we estimate it is no longer operational. Its last test launch took place in February 2018 and it was last mentioned in official Indian Navy announcements in June 2019. It was also included in the US Air Force’s National Air and Space Intelligence Center report on ballistic and cruise missiles in 2020 (National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2020). Since then, however, both the Subhadra and Suvarna have been pictured making international port visits with their missile stabilizer platforms removed, and satellite imagery indicates that the platforms had not been reinstated as of July 2024 (see Figure 2). As a result, we assess that the Dhanush is no longer operational with the Indian Navy.

Although India’s sea-based deterrent remains largely in its infancy, the country clearly retains an ambition to field a sophisticated naval nuclear deterrent force centered around new nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines, long-range sea-based ballistic missiles, and a large new naval base.

India’s first indigenous nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN), INS Arihant (previously known under the project designation as S2, and now with the hull number SSBN-80), was commissioned in August 2016 but spent most of 2017 and the first half of 2018 undergoing repairs after its propulsion system was crippled by water damage (Peri and Joseph 2018). In November 2018, Prime Minister Modi announced that INS Arihant had completed its first deterrence patrol, officially marking the completion of India’s nuclear triad. He additionally stated that the deployment constituted “a fitting response to those who indulge in nuclear blackmail” (R. Singh 2018). The “deterrence patrol” lasted approximately 20?days, and the phrasing would imply that nuclear weapons may have been carried onboard during the patrol; however, this cannot be confirmed through open sources. INS Arihant appears to bear a strong resemblance to the Russian-built Kilo-class attack submarines that are operated by the Indian Navy, with the exception that it is nuclear-powered and has a unique missile compartment designed to accommodate up to 12 nuclear-capable K-15 submarine-launched ballistic missiles in four tubes (Sutton 2021).

It is likely that INS Arihant will primarily serve as a training vessel and technology demonstrator (Gady 2018). This claim is further bolstered by the fact that the Arihant has rarely been seen, photographed, or written about in recent years, despite it being a significant technological achievement for India’s Navy (Sutton 2021). The submarine was most recently used as a test launch platform in October 2022, when it launched an unnamed SLBM in a “user training launch” (Ministry of Defence 2022).

A second SSBN, the INS Arighat (designated S3 and previously intended to be named INS Aridhaman), was launched on November 19, 2017 and was expected to be commissioned into the Indian Navy in 2020 (Pubby 2020). However, the Arighat did not begin sea trials until the beginning of 2022 and was just recently commissioned into service on August 29, 2024 (Janes 2024; Ministry of Defence 2024). Satellite imagery indicates that both the Arihant and the Arighat possess four missile tubes and appear to have identical dimensions.

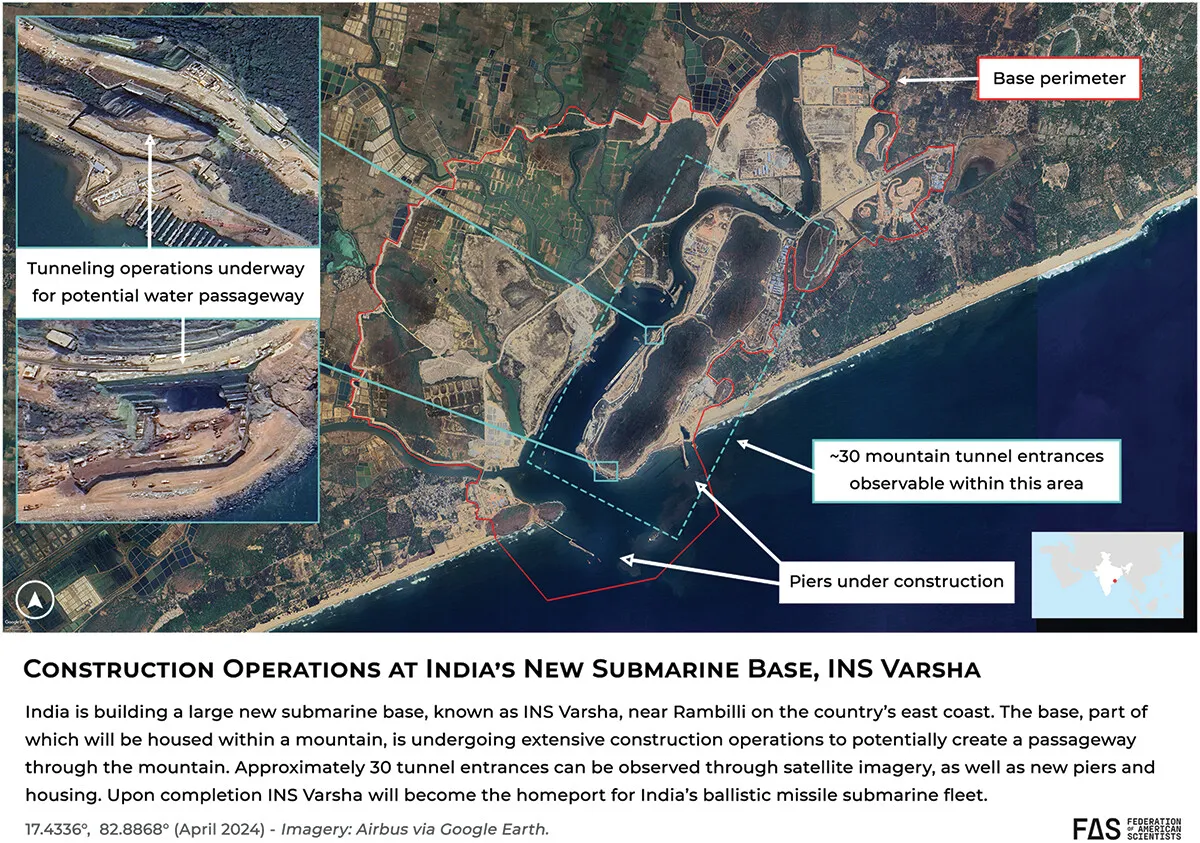

The Arighat will be followed by two more SSBNs of the same class, temporarily designated S4 and S4* (Bedi 2017), which were scheduled to enter service before 2024, but have also been delayed (Pubby 2020). The first of these, the S4, was launched in November 2021, and is noticeably longer and wider than India’s first two SSBNs (Biggers 2021). Satellite imagery indicates that the S4 is approximately 16 to 18 meters longer than the first two SSBNs and equipped with eight missile tubes—twice the number present on the Arihant and Arighat (see Figure 3).

India is also developing its next generation of SSBNs—the S5 class. A series of tweets by the Indian vice president during his visit to the country’s Naval Science & Technology Laboratory revealed some details about what this new class of submarines might look like (Vice President of India 2019). Photos indicate that the new submarines will be significantly larger than the current Arihant-class and could have 12 or more launch tubes (Sutton 2019). This new class of submarines could begin production after the completion of all four Arihant-class boats in the late 2020s, and a large new shipbuilding hall is currently under construction at Visakhapatnam—possibly to accommodate this new project.

A naval base for the SSBNs, named INS Varsha, is currently under construction near Rambilli on the Indian east coast—only 50 kilometers from the Visakhapatnam shipyard where India builds its submarines. It will be located near a facility under construction that is associated with the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre—India’s primary nuclear research institution, which is also tied to its nuclear weapons program. INS Varsha is undergoing extensive construction with numerous tunnels into a mountain, large piers, and support facilities. Satellite imagery show construction of what appears to be two water entrances into a large underground tunnel complex, possibly for ballistic missile loading of submarines, as well as several land-based entry points (see Figure 4).

To arm its SSBNs, India has developed one nuclear-capable sea-launched ballistic missile and is working on another: the current K-15 (also known as Sagarika or B-05) submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) with a range of 700 kilometers and the future K-4 SLBM with a range of about 3,500 kilometers. The relatively short range of the K-15 would not allow the SSBNs to target Islamabad—only southern Pakistan—and the submarines would not be able to target China at all unless they sailed through the Singapore Strait, deep into the South China Sea. Therefore, despite its induction in the summer of 2018, the K-15 should be seen primarily as an intermediate program intended to develop the technology for more capable future missiles.

The K-4, which reportedly has similar characteristics to the Agni-III intermediate-range ballistic missile, has undergone at least eight test launches, the two most recent of which reportedly took place only six days apart in December 2023 from submersible pontoons (Pandit 2023). The missile appears to be nearly ready for serial production (Pandit 2023). A 2015 launch video of the K-4 SLBM indicated that rather than the cold launch system typically used by most SLBMs—through which the missile gets ejected from the launch tube via a gas generator—the K-4 uses two small motors on the front end of the missile to pull it several meters above the surface of the water before the main engine ignites (DRDO 2015). However, it is possible that this is due to the launch platform that was used for the 2015 test, before India had deployed its first ballistic missile submarine, rather than how the missile would be deployed in an operational context.

Rumors about the K-4 claim that it is highly accurate, reaching “near zero circular error probability,” according to the Defence Research and Development Organisation (Panda 2016), and one official reportedly claimed: “Our Circular Error Probability is much more sophisticated than Chinese missiles” (Peri 2020). Such claims, however, should probably be taken with a grain of salt. With a range of 3,500 kilometers, the K-4 will be able to target all of Pakistan and most of China from the northern Bay of Bengal. Each SSBN launch tube will be capable of carrying either one K-4 or three K-15s. As is usual with Indian nuclear programs in the absence of official statements, rumors and speculation posit that each K-4 SLBM will be capable of carrying more than one warhead, but that seems highly unlikely given the missile’s limited capability.

In addition, senior Indian defense officials have stated that the Defence Research and Development Organisation is reportedly planning to develop a 5,000-kilometer range SLBM that matches the design of the land-based Agni-V and would allow Indian submarines to target all of Asia, parts of Africa, Europe, and the Indo-Pacific region, including the South China Sea. The missile will reportedly be called the K-5 and was initially expected to be tested sometime in 2022 (Gupta 2020), although as of July 2024 no such launch had still taken place.

Cruise missiles

India’s first indigenously-produced cruise missile—the Nirbhay—looks similar to the American Tomahawk or the Pakistani Babur. The Indian Ministry of Defence describes the Nirbhay as “India’s first indigenously designed and developed long-range subsonic cruise missile having 1,000-kilometer range and capable of carrying up to 300-kilogram warheads” (Ministry of Defence 2019, 100). India has reportedly completed development trials of the Nirbhay (Gupta 2023). Although there are many rumors that the Nirbhay is dual-capable, with some sources asserting that the Nirbhay is capable of carrying a 450-kilogram conventional or 12-kiloton nuclear payload (Defense Project 2024; Hindustan Times 2024), neither the Indian government nor the US intelligence community has publicly corroborated these statements. The DRDO confirmed in early 2020 that additional variants of the Nirbhay cruise missile were in the early stages of planning and development (Udoshi 2020). According to a DRDO poster released by the news agency Asian News International in November 2023, a trial of a submarine-launched Nirbhay derivative—with land attack and anti-ship variants—was successfully conducted in February 2023 at a range of 402 kilometers (Menon 2023).

Another Nirbhay derivative under development by DRDO is the supersonic Indigenous Technology Cruise Missile (ITCM). According to Janes, the ITCM is a technology demonstrator program for testing the capability of India’s indigenous small turbofan engines, known as the “Manik,” and other subsystems. A DRDO official reported that a March 2023 flight test of the ITCM successfully demonstrated the capabilities of the new engine, adding that the test paved the way for integration of the engine into another cruise missile under development: the Long-Range Land Attack Cruise Missile (LRLACM) (Janes 2023a). The LRLACM is intended to replace the Nirbhay and will be operated by all three branches of the Indian military. In 2023, Janes reported that the DRDO designated the LRLACM as nuclear-capable, but this has not been confirmed publicly by Indian officials or US Intelligence sources (Janes 2023b).

India’s Defence Acquisition Council accorded an Acceptance of Necessity (AoN) to procure the LRLACM in August 2023 (Janes 2023b). India’s Ministry of Defence reported another successful test flight of a Manik-powered ITCM in April 2024, demonstrating low-altitude flight and the successful performance of enhanced radio frequency seekers and other subsystems (M. Singh 2024).

This research was carried out with grants from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Jubitz Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

References

Abbasi, A. 2019. “Hope India Knows What NCA Means?” The News International. Accessed February 27. https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/437316-hope-india-knows-what-nca-means

Albright, D. 1998. “The Shots Heard ‘Round the World.” The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 54 (4): 20–25. Accessed July/August. https://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/Albright1998Shots.pdf

BBC. 2021. “Ladakh: China Reveals Soldier Deaths in India Border Clash.” Accessed February 19. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-56121781

Bedi, R. 2017. “India Quietly Launches Second SSBN.” Janes Defence Weekly. Accessed December 11. https://web.archive.org/web/20180223170149/https://www.janes.com/article/76315/india-quietly-launches-second-ssbn

Bhatt, M. 2022. “The Curious Case of a Misfired Missile.” DNA India: kistan–2939848. Accessed March 14. https://www.dnaindia.com/analysis/report-the-curious-case-of-a-misfired-missile-india-

Biggers, C. ( @CSBiggers).2021. “India Quietly Launched S4 in November 2021 at SBC. Details in My Next @janesintel Report which is Now Live for Subscribers. (Imagery: @planet).” Twitter. Accessed December 28. https://twitter.com/CSBiggers/status/1476048094580117509

Dawn. 2022. “NSA Yusuf Questions India’s Ability to Handle Sensitive Technology After Missile Accident.” Accessed March 11. https://www.dawn.com/news/1679447

Defense Project, Missile 2024. “Nirbhay.” Center for Strategic and International Studies. Accessed April 23. https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/nirbhay/

Department of Atomic Energy. 2024. “PM Witnesses the Historic ‘Commencement of Core Loading’ at India’s First Indigenous Fast Breeder Reactor (500 MWe) at Kalpakkam, Tamil Nadu.” Accessed March 4. https://dae.gov.in/pm-witnesses-the-historic-commencement-of-core-loading-at-indias-first-indigenous-fast-breeder-reactor-500-mwe-at-kalpakkam-tamil-nadu/

Desai, J. 2022. “Understanding the AGNI-P Missile Test by India.” Center for Air Power Studies. Accessed December 12. https://capsindia.org/understanding-the-agni-p-missile-test-by-india/

Dominguez, G. 2019. “Dassault Aviation Releases Images of Second Rafale Aircraft for Indian Air Force.” Janes Defence Weekly. Accessed October 11. https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/dassault-aviation-releases-images-of-second-rafale-aircraft-for-indian-air-force

DRDO. 2015. “Our Recent Achievements: From Strategic and Tactical Systems to Technology Spin-Offs.” Film for AeroIndia. Accessed March. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2O7iOp1nIcc

DRDO Newsletter. 2014. “TCT-5 Performs Excellently in Missile Ejection Test.” Accessed June. https://web.archive.org/web/20140723084909/http://drdo.gov.in/drdo/pub/newsletter/2014/june_14.pdf

Dubey, A. K. 2023. “After Pralay, Defence Forces May Opt for Medium-Range Ballistic Missiles in Conventional Roles for Rocket Force.” ANI. Accessed November 5. https://www.aninews.in/news/national/general-news/after-pralay-defence-forces-may-opt-for-medium-range-ballistic-missiles-in-conventional-roles-for-rocket-force20231105195450/

The Economic Times. 2024a. “India, France to Begin Negotiations This Week in Mega Rs 50,000 Crore 26 Rafale Marine Jet Deal.” Accessed May 28. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/india-france-to-begin-negotiations-this-week-in-mega-rs-50000-crore-26-rafale-marine-jet-deal/articleshow/110493857.cms

The Economic Times. 2024b. “India Successfully Conducts Night Trial of New-Generation Agni-Prime Ballistic Missile; Boosts Strategic Deterrence.” Accessed April 4. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/sme-sector/strategic-insights-flourish-at-et-make-in-india-sme-summits-kolkata-chapter/articleshow/110934004.cms

Frieß, F., M. Kütt, Z. Mian, and P. Podvig. 2024. “Global Stocks and Production of Fissile Materials, 2023.” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Annual Yearbook 2024. Accessed June 17. https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/YB24%2007%20WNF.pdf

Gady, F.-S. 2018. “India Test Fires Short-Range Ballistic Missiles from Submerged Sub.” The Diplomat. Accessed August 22. https://thediplomat.com/2018/08/india-test-fires-short-range-ballistic-missiles-from-submerged-sub/

Ghosh, D. 2016. Successful Test Launch of AGNI V. Press Information Bureau, Government of India. Accessed December 27. http://pib.nic.in/newsite/printrelease.aspx?relid=155897

Government of India. 2016. “Notification G.S.R. 673(E).” The Gazette of India. Accessed July 8. https://documents.doptcirculars.nic.in/D2/D02rti/SFC-08072016.pdf

Government of India. 2021a. “DRDO Successfully Conducts Second Flight-Test of Indigenously Developed Conventional Surface-To-Surface Missile ‘Pralay’.” Indian Ministry of Defence. Accessed December 23. https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1784515

Government of India. 2021b. “New Generation Ballistic Missile ‘Agni P’ Successfully Test-Fired by DRDO.” Indian Ministry of Defence. Accessed December 18. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1782960

Government of India. 2022. “Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile, Agni-4, Successfully Tested.” Indian Ministry of Defence. Accessed June 6. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1831654

Government of India. 2023a. “Indian Ministry of Defence, ‘Successful Training Launch of Agni-1 Ballistic Missile.” Indian Ministry of Defence. Accessed June 1. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1929176

Government of India. 2023b. “Successful Training Launch of Short-Range Ballistic Missile, Prithvi-II, Carried Out off Odisha Coast.” Indian Ministry of Defence. Accessed January 10. https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1890129

Government of India. 2024. “DRDO Successfully Conducts Mission Divyastra: Indigenously Developed Agni-5 Missile Makes Maiden Flight with MIRV.” Indian Ministry of Defense. Accessed March 11. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2013549

Gupta, S. 2018. “Agni-V Set to Be Inducted by December After One More Test.” Hindustan Times. Accessed August 14. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/agni-v-to-undergo-one-more-pre-induction-test/story-a9OcIgjWaRUyMbBoSOnM5M.html

Gupta, S. 2020. “India Plans 5,000-Km Range Submarine- Launched Ballistic Missile.” Hindustan Times. Accessed January 26. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-plans-5-000-km-range-ballistic-missile/story-bystz09QSaHJwYvAtlbNeI.html

Gupta, S. 2023. “Nuke Triad Proven, India to Build Conventional Missile Deterrent.” Hindustan Times. Accessed April 17. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/nuke-triad-proven-india-to-build-conventional-missile-deterrent-101681711263371.html

Gupta, S. 2024. “Rafale’s Make-In-India Plans Get Shot in the Arm.” Hindustan Times. Accessed July 2. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/rafales-make-in-india-plans-get-shot-in-the-arm-101719896115568.html

The Hindu. 2019. “DRDO Successfully Conducts Agni II Missile’s Night Trial for First Time.” Accessed November 16. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/agni-ii-missile-drdo-successfully-conducts-night-trial-for-first-time/article29993943.ece

Hindustan Times. 2022. “France Hands Over 3 Rafale Fighter Jets with India-Specific Enhancements to IAF.” Accessed February 1. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/france-hands-over-3-rafale-fighter-jets-with-india-specific-enhancements-to-iaf-101643711222359.html

Hindustan Times. 2024. “On Cam: Made-In-India Nirbhay Cruise Missile Flies High Powered by Indian Engine | Watch.” Accessed April 18. https://www.hindustantimes.com/videos/news/on-cam-made-in-india-nirbhay-cruise-missile-flies-high-powered-by-indian-engine-watch-101713450714936.html

Hindustan Times. 2024a. “India Discusses Purchase of 12 Used Mirage-2000 Fighter Aircraft from Qatar.” Accessed June 22. https://www.hindustantimes.com/business/india-discusses-purchase-of-12-used-mirage-2000-fighter-aircraft-from-qatar-101719050977803.html

Inamdar, N., and Y. Joshi. 2023. “Honey-Trapped DRDO Scientist Shared Details of India’s Missile, Drone Programmes.” Hindustan Times. Accessed July 8. https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/mumbai-news/pune-scientist-arrested-for-espionage-shared-sensitive-missile-and-drone-details-with-pakistani-operative-101688757246133.html

Indian Air Force. 2021. “Air Chief Marshal RKS Bhadauria, CAS Formally Inducted Rafale Aircraft into No. 101 Sqn at AFS Hasimara in Eastern Air Command (EAC) on 28 July the Event Included a Flypast and a Traditional Water Cannon Salute.” Twitter. Accessed July 28. https://x.com/IAF_MCC/status/1420375697558675463

Janes. 2023a. “Cruise Control: India Accelerates Development of Tactical Missiles.” Accessed March 9. https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-news/defence/cruise-control-india-accelerates-development-of-tactical-missiles

Janes. 2023b. “India Approves AoN to Acquire Long-Range Land Attack Cruise Missile.” Accessed August 25. https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-news/defence/india-approves-aon-to-acquire-long-range-land-attack-cruise-missile

Janes. 2024. “India to Commission Second Nuclear Submarine by End of 2024.” Accessed May 28. https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-news/sea/india-to-commission-second-nuclear-submarine-by-end-of-2024

Jha, S. 2020. “India’s DRDO Scrams into Military Hypersonic Club with Successful HSTDV Test.” Delhi Defence Review. Accessed September 7. https://delhidefencereview.com/2020/09/07/indias-drdo-scrams-into-military-hypersonic-club-with-successful-hstdv-test/

Korda, M. 2022. “Flying Under the Radar: A Missile Accident in South Asia.” FAS Strategic Security Blog. Accessed April 4. https://fas.org/blogs/security/2022/04/flying-under-the-radar-a-missile-accident-in-south-asia/

Korda, M., and H. M. Kristensen. 2021. “India’s Nuclear Arsenal Takes a Big Step Forward.” FAS Strategic Security Blog. Accessed December 23. https://fas.org/blogs/security/2021/12/indias-nuclear-arsenal-takes-a-big-step-forward/

Kristensen, H. M. 2013. “India’s Missile Modernization Beyond Minimum Deterrence.” FAS Strategic Security Blog. Accessed October 4. https://fas.org/blogs/security/2013/10/indianmirv/

Kristensen, H. M., and M. Korda. 2022. “Indian Nuclear Weapons, 2022.” The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists78 (4): 4, 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2022.2087385.

Kristensen, H. M., and M. Korda. 2024. “Indian Test-Launch of MIRV Missile Latest Sign of Emerging Nuclear Arms Race.” FAS Strategic Security Blog. Accessed March 12. https://fas.org/publication/indian-test-launch-of-mirv-missile-latest-sign-of-emerging-nuclear-arms-race/

Kumar, P. 2018. “Kalpakkam Fast Breeder Test Reactor Achieves 30 MW Power Production.” Times of India. Accessed March 27. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/kalpakkam-fast-breeder-test-reactor-achieves-30-mw-power-production/articleshow/63480884.cms

Kunde, R. 2023. “IAF Draws Up Jaguar Retirement Plans.” Indian Defence Research Wing. Accessed May 19. https://idrw.org/iaf-draws-up-jaguar-retirement-plans/

Levy, A. 2015. “India is Building a Top-Secret Nuclear City to Produce Thermonuclear Weapons, Experts Say.” Foreign Policy. Accessed December 16. http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/12/16/india_nuclear_city_top_secret_china_pakistan_barc/

Liu, G. 2018. “Missed Missiles: Finding a Failed Missile Test in India.” Arms Control Wonk. Accessed October 23. https://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/1206159/missed-missiles-finding-a-failed-missile-test-in-india/

Menon, A. 2023. “India Focuses on Long Range Naval Missiles Development.” Naval News. Accessed December 14. https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2023/12/india-focuses-on-long-range-naval-missiles-development/

Ministry of Defence. 2014. Annual Report 2013–14: 86. http://mod.nic.in/writereaddata/AnnualReport2013-14-ENG.pdf

Ministry of Defence. 2017. Annual Report 2016–17: 38. http://mod.nic.in/writereaddata/AnnualReport1617.pdf

Ministry of Defence. 2019. Annual Report 2018-19. https://mod.gov.in/sites/default/files/MoDAR2018.pdf

Ministry of Defence. 2022. “INS Arihant Carries Out Successful Launch of Submarine Launched Ballistic Missile.” Press Information Bureau, release number 1867778, Accessed October 14. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1867778

Ministry of Defence. 2024. “Second Arihant-class Submarine ‘INS Arighaat’ Commissioned into Indian Navy in the Presence of Raksha Mantri in Visakhapatnam.” Press Information Bureau, release number 2049870, August 29. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2049870

Narang, V. 2013. “Five Myths About India’s Nuclear Posture.” The Washington Quarterly36 (3): 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2013.825555.

Narang, V. 2017. “Remarks by Professor Vipin Narang, Department of Political Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.” At the Carnegie International Nuclear Policy Conference., Washington, D.C. [], Accessed March 20. https://fbfy83yid9j1dqsev3zq0w8n-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Vipin-Narang-Remarks-Carnegie-Nukefest-2017.pdf

National Air and Space Intelligence Center. 2020. “Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat.” United States Air Force. Accessed January. https://media.defense.gov/2021/Jan/11/2002563190/-1/-1/1/2020%20BALLISTIC%20AND%20CRUISE%20MISSILE%20THREAT_FINAL_2OCT_REDUCEDFILE.PDF

Panda, A. 2016. “India Successfully Test Intermediate-Range Nuclear-Capable Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missile.” The Diplomat. Accessed April 10. https://thediplomat.com/2016/04/india-successfully-tests-intermediate-range-nuclear-capable-submarine-launched-ballistic-missile/

Pandit, R. 2023. “Arihant’s N-Capable Missile ‘Ready to roll’.” Times of India. Accessed December 14. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/india-successfully-test-fires-k-4-submarine-launched-missile/articleshow/73589861.cms

Peri, D. 2020. “India Successfully Test-Fires 3,500-Km Range Submarine-Launched Ballistic Missile K-4.” The Hindu. Accessed January 19. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-successfully-test-fires-3500-km-k-4-slbm/article30601739.ece

Peri, D., and J. Joseph. 2018. “INS Arihant Left Crippled After ‘Accident’ 10 Months Ago.” The Hindu. Accessed January 8. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/ins-arihant-left-crippled-after-accident-10-months-ago/article22392049.ece

Philip, S. A. 2021. “Why Pralay Quasi-Ballistic Missile, Tested by DRDO Today, Will Be a ‘Game-changer’ for Army.” The Print. Accessed December 22. https://theprint.in/defence/why-pralay-quasi-ballistic-missile-tested-by-drdo-today-will-be-a-game-changer-for-army/785809/

Philip, S. A. 2022. “Why India is Set to Miss 2021 Deadline to Upgrade Mirage 2000 Fighters.” The Print. Accessed October 7. https://theprint.in/defence/why-india-is-set-to-miss-2021-deadline-to-upgrade-mirage-2000-fighters/746444/

Press Information Bureau. 2013. “Prithvi Does it Again.” PIB Release/dl/1408. Accessed October 8. http://www.pibmumbai.gov.in/scripts/detail.asp?releaseId=E2013PR1649

Pubby, M. 2020. “India’s Rs 1.2 Lakh Crore Nuclear Submarine Project Closer to Realisation.” The Economic Times. Accessed February 21. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/indias-rs-1-2-l-cr-n-submarine-project-closer-to-realisation/articleshow/74234776.cms

Rout, H. K. 2022. “Agni III Missile Night Trial Successful.” The New Indian Express. Accessed November 23. https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2022/Nov/24/agni-iii-missile-night-trial-successful-2521605.html

Sarkar, A. 2021. “What’s Known—And Not Known—About India’s Nuclear Weapons Budget.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Accessed November 2. https://thebulletin.org/2021/11/whats-known-and-not-known-about-indias-nuclear-weapons-budget/

Sen, S. R. 2021. “India Defense Chief Says China is the ‘Biggest Security Threat’.” Bloomberg. Accessed November 12. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-11-12/india-defense-chief-says-china-is-the-biggest-security-threat

Shukla, A. 2016. “Cutting-Edge Agni Technologies to Add Teeth to Pakistan-Focused Nuclear Deterrent.” Business Standard. Accessed December 17. https://www.ajaishukla.com/2016/12/cutting-edge-agni-technologies-to-add.html

Shukla, A. 2019. “Air Force Chief Outlines Plan to Solve Shortage of Fighter Squadrons.” Business Standard. Accessed October 5. https://www.business-standard.com/article/defence/air-force-chief-outlines-plan-to-solve-shortage-of-fighter-squadrons-119100401549_1.html

Shukla, A. 2021a. “Cost Vs Combat Edge: Future of IAF’s Jaguar Fleet is Hanging in the Balance.” Business Standard. Accessed June 18. https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/cost-vs-combat-edge-future-of-iaf-s-jaguar-fleet-is-hanging-in-the-balance-121061800014_1.html

Shukla, A. 2021b. “Pakistan-Aimed Agni-P Ballistic Missile Flight-Tested Successfully.” Business Standard. Accessed June 29. https://www.ajaishukla.com/2021/06/pakistan-aimed-agni-p-ballistic-missile.html

Singh, M. 2024. “Nirbhay Cruise Missile Advances Signal India’s Growing Defense Capabilities.” Indo-Pacific Defense Forum. Accessed May 29. https://ipdefenseforum.com/2024/05/nirbhay-cruise-missile-advances-signal-indias-growing-defense-capabilities/

Singh, R. 2018. “India Completes Nuclear Triad with INS Arihant’s First Patrol.” Hindustan Times. Accessed November 6. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/fitting-response-to-nuke-blackmail-says-pm-on-ins-arihant-s-first-deterrence-patrol/story-SDGODa4nxf6NfevT5davtJ.html

Singh, R. 2019. “Pokhran is the Area which Witnessed Atal Ji’s Firm Resolve to Make India a Nuclear Power and Yet Remain Firmly Committed to the Doctrine of ‘No First Use.’ India Has Strictly Adhered to This Doctrine. What Happens in Future Depends on the Circumstances.” Twitter. Accessed August 16. https://twitter.com/rajnathsingh/status/1162276901055893504

Som, V. 2016. “Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar’s Nuclear Remark Stressed as ‘Personal Opinion’.” NDTV. Accessed November 10. http://www.ndtv.com/india-news/defence-minister-manohar-parrikars-nuclear-remark-stressed-as-personal-opinion-1623952

Sundaram, K., and M. V. Ramana. 2018. “India and the Policy of No First Use of Nuclear Weapons.” Journal for Peace & Nuclear Disarmament1 (1): 152–168. p.153. https://doi.org/10.1080/25751654.2018.1438737.

Sutton, H. I. 2019. “Indian Next Generation S-5 SSBN Revealed.” Covert Shores, September 2. http://www.hisutton.com/S-5_SSBN.html

Sutton, H. I. 2021. “5 Years of Submarine Secrecy: India’s Unique Arihant Class is Still in Hiding.” Naval News. Accessed May 5. https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2021/05/5-years-of-submarine-secrecy-indias-unique-arihant-class-is-still-in-hiding/

Thakur, V. K. 2024. “India’s New Agni Prime Missile Demonstrates Technological Advances.” Sputnik India. Accessed June 21. https://sputniknews.in/20240621/indias-new-agni-prime-missile-demonstrates-technological-advances-7675551.html

Times of India. 2013. “India Can Develop 10,000 Km Range Missile: DRDO.” Accessed September 16. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/india-can-develop-10000km-range-missile-drdo/articleshow/22633920.cms

Udoshi, R. 2020. “Defexpo 2020: India to Test Nirbhay Cruise Missile Powered by Indigenous Propulsion System.” Janes Defence Weekly. Accessed February 6. https://www.janes.com/defence-news/news-detail/defexpo-2020-india-to-test-nirbhay-cruise-missile-powered-by-indigenous-propulsion-system

Unnithan, S. 2021. “The ‘K’ Factor in the Recent Missile Tests.” India Today. Accessed December 30. https://www.indiatoday.in/india-today-insight/story/the-k-factor-in-the-recent-missile-tests-1894315-2021-12-30

Vice President of India. 2019. “Went Around an Exhibition Displaying Naval Weapons and Systems at Naval Science & Technological Laboratory (NSTL), DRDO at Vizag, Andhra Pradesh Today. I Am Here to Participate in the Golden Jubilee Celebrations of NSTL. @drdo_india.” Twitter. Accessed August 28. https://twitter.com/VPSecretariat/status/1166582964051951616

Yelwe, R. 2024. “Lessons Learned from India’s Struggle to Maintain the Mirage 2000.” The Diplomat. Accessed March 9. https://thediplomat.com/2024/03/lessons-learned-from-indias-struggle-to-maintain-the-mirage-2000/