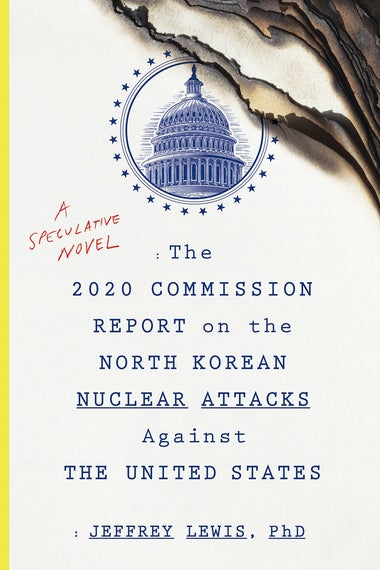

A new novel tells the story behind the terrible U.S.–North Korea war of 2020.

The title of Jeffrey Lewis’ new novel, The 2020 Commission Report on the North Korean Nuclear Attacks Against the United States, gives you a pretty good idea of what’s inside. Written in the style of the 9/11 Commission Report, it recounts a disturbingly plausible series of events that lead to the governments of U.S. President Donald Trump, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, and South Korean President Moon Jae-in starting a nuclear war that kills millions of people in Asia and the United States.

In the year 2020, as imagined by the book with painstaking detail and bleak humor, the current era of good feelings between the U.S. and North Korea has ended and Trump has returned to his “little rocket man” taunts. The crisis begins when North Korea shoots down a South Korean civilian airliner, mistaking it for a bomber—an incident with a real-world precedent. An unexpectedly aggressive military response from South Korea combined with an ill-timed tweet from Trump, while on his way to a tee time in Mar-a-Lago, to make Kim believe he is under attack and that a nuclear strike is his only option for survival.

Lewis, a blogger, columnist at Foreign Policy, and scholar at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies, is a leading authority on nuclear weapons, frequently quoted in news articles about the North Korea crisis. The book’s realism is heightened by his detailed descriptions of the safeguards and strategies in place to prevent a nuclear catastrophe—and how they break down—as well as real quotations from survivors of the Hiroshima attacks, repurposed to tell the story of the aftermath of a modern-day nuclear strike.

I spoke with Lewis about why we underestimate the risk of nuclear war, why we overestimate how much that risk has to do with Trump himself, and why recent events haven’t made him any less worried. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Joshua Keating: I was surprised by how up to date the timeline in the book is. But you didn’t quite get the Singapore summit in there. Has anything that has happened since changed your views on how likely this scenario is?

Jeffrey Lewis: No. In fact, kind of the opposite. It was very funny because when the summit was announced, the publicity people were like, maybe we won’t publish the book now because Kim Jong-un’s going to give up his nuclear weapons. And I was like, did you read the book? This is literally what happens in the book. Then, of course, things started to get complicated.

But other than your overall views, are there things that have happened since you finished writing that you wish you could have included?

Definitely the thing about Trump not understanding time zones. I would have made so much hay with that, but if I had invented it, no one would have believed it. I would have had that be a consequential plot point, that he literally couldn’t understand that the Earth was round and that it was warm and sunny here and the middle of the night there.

But for all that Trump and his Twitter account play a major role in the story, a lot of the events that lead up to your nuclear war are kind of independent of him: the shoot-down of the plane, how South Korea responds, how Mattis responds. Do you think that sometimes Trump makes us understate the risks that are there regardless of who is president?

Yes, that is exactly the point. Trump sheds a light on all these risks that we live with every day. He makes us question how well our institutions are designed. And the fact is, they’re not that well-designed. We’ve gotten really lucky in the past. Trump helps us focus on what happens when that luck runs out.

As much as I don’t like the man, in the book I kind of treat him more as a force of nature than as some kind of malign personality. It’s clear throughout the book that at no point is he interested in a war. He feels pushed and pressed. He’s never a deliberate actor who puts in place a plan that comes to fruition. He thrashes about, and it’s all the movements around him that generate the nuclear war.

Right, although as bad as things get in the book, at one point you hint that it could get even worse when the president is talking about bombing China as well. Were you ever tempted to go full apocalyptic with this?

The fact is that the North Korean arsenal is only a certain size and could only be a certain size by 2020. I felt like the war was always going to be limited, which then frees me to have this commission. Without spoiling anything, when you get to the end, I don’t envision a dystopia. It looks shockingly like the situation now. It’s almost like you go through this and say, “Oh my God, we’re kind of in the dystopia already.”

The accounts of the victims of the nuclear blasts in the book are all taken from testimonies of Hiroshima victims, right?

Yeah, they’re all from Hiroshima. I’m a member of the governor of Hiroshima’s roundtable on disarmament, so I go every year. That’s a really important experience for me. I find that the real testimonies are incredibly moving, and it didn’t feel right to make up stories of suffering when there already are such stories. And I’d like more people to engage with that literature, which I know can be hard. I’m hoping that at least some portion of readers go back to the originals. If they can’t contemplate this happening to them, maybe they can think about people it did happen to and consider different choices they could make.

One thing I found kind of refreshing in the book is the depiction of North Korean leaders as basically rational, even if they have some disturbing ideas. I wonder if the depictions of the North Koreans as wacky and crazy in both news coverage and pop culture has played some role in us underestimating the nuclear threat.

Hmm. I think the word you’re looking for is “racism”! I started my career working on China’s nuclear program. And I was struck that when I would go to China and interview people involved in their program about the choices they’d made and the historical reasons for them, and then I’d come back to the U.S. and talk about China’s nuclear weapons program—it was like talking about two different countries.

I struggled here at the Middlebury Institute when we did open-source research on the reasons why North Korea developed nuclear weapons. People were pretty resistant to imagining that the North Koreans had their own ideas about why they need nuclear weapons. We all say, “Oh, those ideas are crazy.” But you know what? Our ideas are crazy, too. Pretty much everyone’s ideas about nuclear weapons are insane.

When you step back you can see that two groups of people with crazy ideas about nuclear weapons, even if they’re being “rational” in a narrow sense, the system as a whole is chaotic.

Does the China comparison suggest how we will one day look at North Korea’s weapons as well? Not liking that they have them, but accepting them as a reality?

Yep. To be honest, I think that’s what the North Koreans are bargaining for now. Whenever I say that the North Koreans aren’t going to give up their nuclear weapons, there’s this assumption that I’m therefore against negotiations. I’m for negotiating for something that we might actually achieve. They’re looking for a deal similar to Israel, Pakistan, and India, where they don’t talk about their weapons and we don’t talk about them.

Another passage that really stuck with me was about missile defense and Trump’s belief that it’s 97 percent effective. You suggest in the book that the people around him might be letting him believe that, even though it’s not true, that they prefer he underestimate the danger from North Korea so he doesn’t do anything really stupid like starting a war. Is that something you also think about in trying to make the public aware of this danger? That if people really understood it, they might overreact?

It’s a huge problem in our field. When people are presented with a threat, they either pretend it doesn’t exist, or they freak out and shut down. So you want to present people with accurate information, and you don’t want to trigger this unhelpful responses where they want to bomb everyone or hole up in their bunker. In the book, one way that I tried to do that is to focus on survivor stories. It’s terrible, but there’s a sense that life goes on.

When people are confronted with the problem and our unwillingness to change our behavior, they say that once there’s a nuclear use, people will figure it out. There have already been two nuclear uses, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and we didn’t figure it out then. The commission in the book has two more uses, and it doesn’t figure it out.

We have enough information now. We could start making different choices now.

—

The 2020 Commission Report on the North Korean Nuclear Attacks Against the United States by Jeffrey Lewis. Mariner Books.

Source:- https://slate.com/culture/2018/08/jeffrey-lewis-interview-about-nuclear-war-with-north-korea.html